In a nutshell, for those who plan to only read the first few paragraphs: yes, it IS that bad. Categorically, unequivocally, current research convincingly shows that cannabis use should be avoided during adolescence and early adulthood.

An article entitled Exposure to cannaboids can lead to persistent cognitive and psychiatric disorders(1) was e-published in March 2019 and is due for publication in the European Journal of Pain in August 2019.(1) Written by a team of French medical practitioners and scientists, it reviews and summarises over 50 published papers relevant to the research and debate about whether regular use of cannabis can have detrimental psychological and cognitive effects.

The authors explain how public and political pressures have meant that evidence-based research, which usually carefully analyses and examines risks vs benefits before a substance receives medical approval, has largely been globally bypassed when proposing cannabis for a wide array of medical indications.

Dr Elizabeth Stuyt from the University of Colorado’s Department of Psychiatry, raises similar concerns in her detailed review article, The problem with the current high-potency THC marijuana from the perspective of an addiction psychiatrist.(2) Stuyt points out that many people who voted for the legalisation of cannabis in certain US states thought they were voting to use the same cannabis they experienced in the 1960s to 1980s, without realising that today’s cannabis is an entirely different beast.

This research is particularly relevant for parents of adolescents, who might think that the recent law change in South Africa means that teens using small amounts of cannabis at home or with friends is perhaps OK.

It isn’t and here’s why …

Firstly, current (2019) South African law only allows private use for over-18s.

Regardless of your personal opinion, it is illegal to use cannabis under the age of 18 in South Africa.

The argument that legalising cannabis will reduce the dangerous illicit (illegal) use of this drug has also been shown to be scientifically incorrect. In fact, in the US, medical cannabis laws seem to have led to an increased amount of illicit use – Dr Stuyt’s research indicates that Colorado has shown a 65% increase in illicit adolescent cannabis use since its legalisation for medicinal purposes.(2)

Secondly, regular cannabis use increases the risk of teenagers committing suicide or developing psychotic or psychological disorders in early adulthood and/or later in life.

Over the last 30 years, significant research has confirmed a vastly increased risk of schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, suicide attempts, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, psychosis and social phobia in adolescents who are using cannabis, and in adults who started using cannabis when they were adolescents.

This is not just hearsay; the logic and science behind this argument is strong.

Our brains are still developing during adolescence and early adulthood, reaching maturity at only about age 25. Substances that influence the brain during this critical and vulnerable stage have been shown to have potentially long-lasting effects on the adult brain – and cannabis particularly affects those parts of the brain involved in emotional and psychological development.

Research repeatedly shows that cognitive, psychological or behavioural changes that occur in adolescents who regularly use cannabis may persist indefinitely into adulthood, even once they stop using it.

Thirteen studies now confirm the relationship between cannabis use and the development of schizophrenia later in life. The first was conducted in young Swedish conscripts in 1987.(3) Using cannabis once a week for one year led to a dramatic sixfold increase in the development of schizophrenia by the time they were 35. This risk was increased by a further fourfold in the conscripts who had started using cannabis at age 15!

In Australia, a study that tracked 1 600 girls for seven years found that girls who use cannabis once a week are twice as likely to develop depression compared with non-users. Those who use it daily are five times more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety when compared with non-users.(4)

Numerous studies also confirm the relationship between cannabis use and other psychological conditions. One particularly important publication, entitled Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: an integrative analysis,(5) has amalgamated three long-term studies which were conducted in Australia and New Zealand in 2014. The studies followed a total of approximately 3 000 participants between the ages of 13 and 30. Results show that those who were daily users before age 17 had a sevenfold increase in suicide attempts.(5)

Thirdly, your teenager will underperform at school or university

Evidence confirms that regular cannabis use has a negative impact on cognitive function, especially memory and attention, abstract-thinking ability, decision making, and immediate and delayed verbal recall. This has a profound effect on educational ability and achievement. It also affects sporting prowess and levels of cultural accomplishment(1,2)

A study in New Zealand that followed subjects for an impressive 20-year period, shows an average loss of eight IQ points in teens who regularly and persistently used cannabis.(6) To contextualise this, if your child’s IQ is very high this drop may mean the difference between an A and a B, but if they have an average IQ this may be the difference between average cognitive function and significant cognitive difficulty.

Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: an integrative analysis reports that those who were daily users before age 17 were 63% less likely to finish high school and 62% less likely to obtain a degree.(5)

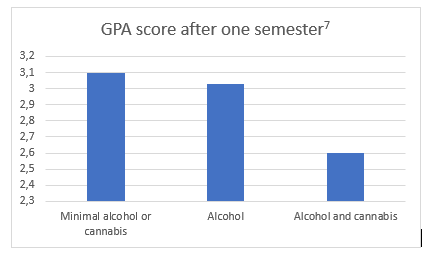

A Yale-based study tracked 1 142 students in the US, all of whom achieved similar college entrance scores (SAT scores) when they enrolled in college. The graph below shows the decline in Grade Point Average (GPA) scores, after only one semester, in those students who were regular substance users.(7)

The GPA scores in this group of students remained lower than the other groups throughout the two years of the study.

The national GPA average in the US is around 3.0, which means that a 2.6 GPA is the equivalent of South African Cs and Ds. This sort of GPA would make it very difficult to complete a college degree.

Fourthly, using cannabis during adolescence increases the chances of becoming addicted to it.

The common adage that cannabis is non-addictive is not true, particularly since today’s cannabis has higher THC concentrations than ever before (read more about this below). There is now no doubt that long-term cannabis use can lead to addiction and, in fact, current findings indicate that approximately 9% of cannabis users will become addicted. This risk increases to one in six in those who start using as a teenager and to a 25-50% risk of addiction for adolescent daily users.(8) Those are risky odds!

But we can now buy ‘CBD’ at health shops or online – surely this means that cannabis is safe to use?

Let’s explain. In simple terms, the cannabis plant is made up of various organic compounds, of which delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) are two of the most well known.

We know that THC is addictive and psychoactive and has significant impact on the areas of the brain that process emotional information, assist learning and memory, and play a role in neuropsychotic disorders such as anxiety, depression, psychosis and schizophrenia.

In contrast, CBD does not have psychoactive effects and is thought to counteract the effects of THC to a degree, which is why many CBD health supplements are now freely available.

The free availability of CBD products, however, has mistakenly led many South Africans to believe that cannabis itself is safe and helpful. But CBD is just one part of the complex cannabis plant; in order to be safe to use, the CBD compound has to be extracted from the rest. ‘Cannabis’ and ‘CBD’ are not the same thing.

Today’s cannabis is not the same as yesterday’s.

Parents who remember being able to enjoy a joint or two with no significant side effects later in life should not assume that their children are being exposed to the same substance when they use cannabis today.

No clear guidelines or legislation currently exist for monitoring THC and CBD content or for how cannabis plants are grown. Therefore, unfortunately, the cannabis industry has copied the alcohol and tobacco industries and developed cannabis plants with significantly higher levels of THC (and correspondingly lower levels of CBD) compared with the cannabis of the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

Prior to the 1990s, most cannabis plants had a THC content of 2%. A landmark study conducted in the UK in 2015 showed that participants using cannabis with a 5% THC concentration did not show psychotic symptoms.(9) It is this ‘less than 5%’ type of cannabis that most adolescents’ parents will remember from their youth.

But during the 90s, first the THC content doubled to 4% and then, research shows, between 1995 and 2015 there was a shocking increase in THC concentration in the cannabis plants and flowers being grown.(2) Not only does this mean that some strains of cannabis now host a 17-28% concentration of THC instead of their original 2%, but the plants have correspondingly low levels of CBD so there is less to help counteract the THC’s addictive and psychotic effects.(2) The 2015 UK study mentioned above shows that participants using cannabis with a concentration of more than 15% THC experienced a three- to fivefold increased risk of psychoses compared to controls who were not using any.(9)

Terrifyingly, some cannabis oils, shatter, dab and edibles on the current market have THC concentrations of up to 95%!(2)

Based on current scientific research and understanding, any way you look at cannabis use, adolescence and early adulthood are periods of vulnerability for long-term cognitive and serious psychiatric consequences.

But surely not everyone who uses cannabis develops a problem?

While this is true, predicting who will and who won’t is difficult. We do, however, know that various risk factors play a role in the likelihood of developing persistent cognitive, psychological or behavioural changes. These include:

- Age: adolescents and young adults are at much higher risk.

- Dosage: how often it is used and how potent the cannabis is. Once a week can probably be regarded as regular use and regular use enhances side effects.

- THC concentration: researchers note an increased frequency in the availability of high-potency cannabis and synthetic cannabis, such as spice or K2, which potentially have heightened side effects.

- Genetic predisposition: psychosis and neuropsychological conditions have a genetic component, which means that cannabis use is more likely to trigger it in some people than in others.

The problem is, neither you nor your teenager may be aware of their genetic predisposition yet, or know what dosage and concentration of cannabis they are using at any given time.

Given the frightening odds of addiction and long-term detrimental psychological and cognitive effects, it seems obvious that it’s best to avoid cannabis use during adolescence and young adulthood completely.

MediComm’s take-home message is this:

If you allow your teenager to use cannabis, or turn a blind eye to what they’re doing when you’re not around, you incur the following risks for them:

- Their academic and sporting ability and performance at school or university is very likely to decline dramatically.

- They have a much greater risk of developing conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety or depression, behavioural changes or suicide attempts later in life.

- Due to the increased THC concentration of modern cannabis, adolescents who use it daily have a 25-50% chance of becoming addicted to it. But even those who experiment with it occasionally are at risk of becoming addicted (particularly if they are adolescents).

- Cognitive, psychological or behavioural changes that occur in adolescents who regularly use cannabis may persist indefinitely into adulthood, even if cannabis use is stopped.

Because of their stage of brain development, adolescents believe they are invincible. Under South Africa’s new cannabis-use laws we need to protect them even more than we did before. It is up to us as adults and parents to educate ourselves and our children, to keep the discussion open and honest and to watch their behaviour carefully: we owe them, and the world they will influence, emotional stability and effective brains in their later years!

A scientific research note …

Specialised clinical studies are required to determine the actual medical benefits of cannabis for specific medical conditions. But significant numbers of these clinical trials have not yet been done. To determine the risk of using the substance in a non-medical setting, we therefore need to use the more than 50 epidemiological* and experimental studies** and various meta-analyses and reviews that have investigated the side effects of regular cannabis use. Through objective analysis of these studies, the authors of Exposure to cannaboids can lead to persistent cognitive and psychiatric disorders and The problem with the current high-potency THC marijuana from the perspective of an addiction psychiatrist have provided useful insights into the long-term effects of cannabis on the user’s cognitive and psychiatric state. It is important to note that, in both cases, the authors of these articles did not benefit from a particular outcome in any way. Their analysis was done to answer a scientific question in a field in which they work daily, not as a marketing exercise. This gives their work credibility.

Footnotes:

*Epidemiology is the study of diseases in populations of humans or other animals, specifically how, when and where they occur. Epidemiologists attempt to determine what factors are associated with diseases (risk factors) and what factors may protect people or animals against disease (protective factors).(10)

**Experimental studies: In an experimental study an independent variable (the cause) is manipulated and the dependent variable (the effect) is measured; any extraneous variables are controlled. An advantage is that experiments should be objective. The views and opinions of the researcher should not affect the results of a study.(11)

References:

- Krebs M‐O, et al. Exposure to Cannabinoids Can Lead to Persistent Cognitive and Psychiatric Disorders. European Journal of Pain, Mar 2019. doi:10.1002/ejp.1377.

- Stuyt E. The Problem With the Current High Potency THC Marijuana From the Perspective of an Addiction Psychiatrist. Missouri Medicine, vol.115, no.6, Nov-Dec 2018, pp. 482–486.

- Andreasson S, et al. Cannabis and Schizophrenia. A Longitudinal Study of Swedish Conscripts.” Lancet, vol. 2, 1987, pp.1483–1486.

- Patton GC. Cannabis Use and Mental Health in Young People: Cohort Study. British Medical Journal, vol. 325, no. 7374, Nov. 2002, pp. 1195–1198. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195.

- Silins E, et al. Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: an integrative analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 1, 2014, pp.286–293.

- Meier MH, et al. Persistent Cannabis Users Show Neuropsychological Decline from Childhood to Midlife. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 109, no.40, Oct. 2012, pp. E2657–2664. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206820109.

- Shashwath A, et al. Longitudinal Influence of Alcohol and Marijuana Use on Academic Performance in College Students. PLOS ONE, vol. 12, no. 3, Mar. 2017, p. e0172213. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172213.

- Volkow ND, et al. Adverse Health Effects of Marijuana Use. New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 370, no. 23, Jun. 2014, pp. 2219–2227. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1402309.

- Di Forti M, et al. Proportion of Patients in South London with First-Episode Psychosis Attributable to Use of High Potency Cannabis: A Case-Control Study. The Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 2, no. 3, Mar. 2015, pp. 233–238. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00117-5.

- Epidemiology [Internet]. [Cited 2019 Jul 26]. Available from: http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/extoxnet/TIB/epidemiology.html

- Experimental methods in psychology [Internet]. [Cited 2019 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.simplypsychology.org/experimental-method.html

0 Comments